I’m not sure how I feel about uncertainty, but I think I’m getting better at it. I’m becoming more comfortable with opinions that agitatedly twitch back and forth like a faulty Geiger counter, especially after a few minutes on online with other people’s certainty (which - to complete the metaphor - often feels like it should come with a hazmat suit).

Opinions are pretty easy to come by. Like the answer to a maths problem, or a finished song, or a dessert, you can just copy the answer from the person sitting next to you, rip off one of Taylor’s middle eights or go to Marks & Spencer and buy the pavlova for which you’ll later claim authorship. The having of an opinion seems to have become the thing; it doesn’t even really matter what it is. One hundred and forty unsolicited characters on why #alllivesmatter and you exist. Nine paragraphs on a Doors album for an Amazon review and you’re immortal. Two and half thousand rambling words in a Substack post? Well, we’ll see.

But if you’re serious about having opinions, what about the the workings-out? Any process, especially one that culminates in an idea that you’re prepared to share with other people, should generate some uncertainty and I’m finding myself more and more drawn to the margins, screwing up my eyes to read those pencil scratches that hang from words like tiny cobwebs. That’s often where you find a human, less concerned with a tidy conclusion, juggling a snake, a family photo from their childhood, an axe, a bible, two bags of weed and a TV remote as they figure shit out.

Something is nagging at me. A line of enquiry has been tugged at one end and the vibrations are keeping me awake. I know myself - if I ignore it, that line will become a network and I’ll end up in one of those tiny stripy tents at the side of the road wearing a high-viz jacket and clutching a fist full of colourful cables with no idea of what connects to what.

Is the spirit of enquiry enough? Proceeding with a more foggy notion of what constitutes a creative intention; kind of working it out as we go along? Is it OK to invite people to join us in this, unable - as we’ll probably be - to offer anything definitive at the end? Lots of art seems comfortable with uncertainty and if art reflects life then uncertainty certainly merits exploring.

I once wrote this, not really thinking about what it meant:

We’ll come to know the letting go.

As I get older, in my creative and cultural life, I’m increasingly drawn to the act of surrender. Not in the sense of defeat, frustration or indifference; more a trust-based backwards topple into a process that the conscious, overthinking, people-pleasing, anxious me hasn’t fucked up yet.

So I’m going to trace a few of those lines; make some tentative connections; satisfy my urge for some gentle dot-joining. If some answers turn up on the way, that’s great, but - to clumsily return to my juggling metaphor - if I end up snakebit and handcuffed to a bed in A&E, that’ll have to be OK too.

***

I’ve just finished a really good book. I say book; it’s really a long essay with photos about the life and work of a doctor servicing a small rural community. I wish I could tell you that his name was Brad Chino - an ex-special forces operative who loses his memory in a helicopter crash over Afghanistan and retrains as a doctor / exorcist on the Mexico border - but that’s just setting you up for disappointment.

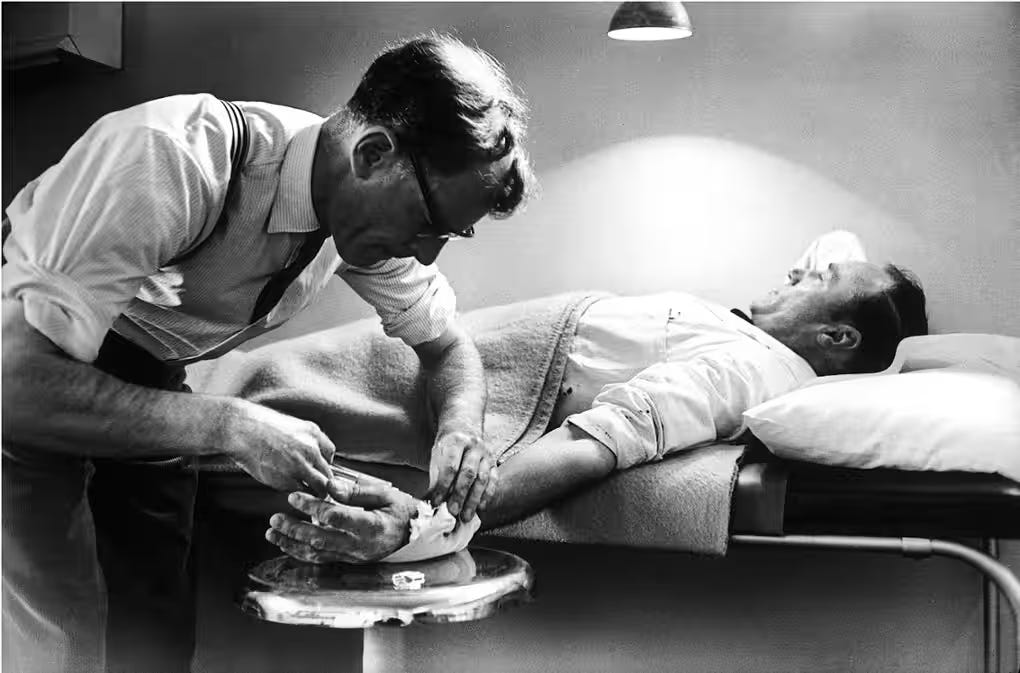

The doctor’s actual name was John Sassall. He worked in a country village in Gloucestershire in the late 60s, smoked a pipe, was no stranger to corduroy and rather liked a round of golf. His particular set of skills seemed to be kindness, decency, a terrifying work ethic and that quiet stoicism that marked so many of a generation trying to come to terms with the all-too-recent memory of a world on fire.

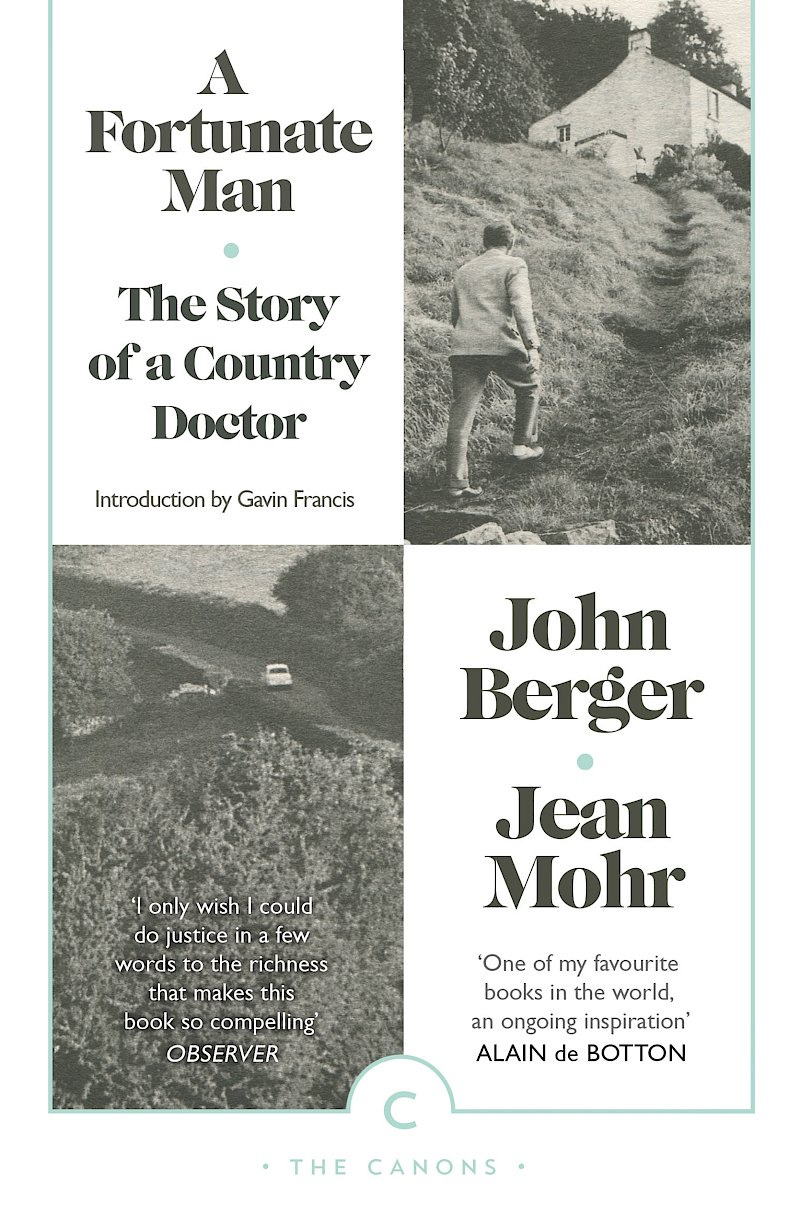

The book is A Fortunate Man: The Story of a Country Doctor by John Berger, with some beautifully candid photographs by Jean Mohr.

Berger was probably most famous for his essay on art criticism, Ways of Seeing, accompanying the BBC TV series of the same name, but he was also a novelist, a painter and a poet. Here though, he uses Sassall’s day-to-day life tending to the needs of a fairly isolated rural community to reflect on the doctor’s motivations, his (largely ignored) needs, his understanding of his role and - more broadly - how society is reflected in these observations. It’s quite a book* and it’s made me think some thoughts that I’d like to share here.

As an act of witness Berger’s account becomes, in a sense, a metaphor for a post-war society lost to itself; a community of traumatised people with little in the way of a common emotional language with which to recognise - let alone express - any of it. One man negotiates this as best he can, trying to ease the burden of lives lived hard, even as his own ghosts hover expectantly around him.

OK, so it’s not a beach read. Depending on the beach I guess.

Where does this emotional vocabulary come from? Berger sums up the post-war, pre-internet emotional lives of this patients like this:

Any general culture acts as a mirror which enables the the individual to recognise himself - or at least to recognise those parts of himself which are socially permissable. The culturally deprived have far fewer ways of recognising themselves. A great deal of their experience - especially emotional and introspective experience - has to remain unnamed for them. Their chief means of expression is consequently through action […] an entirely exterior mechanism or event - a motor car engine, a football match […] The very intricacy of the subjects seems to bring the speakers closer together […] and in their memory this now acquires the value of an intimacy.

Berger writes this in the late 60s, so by his metric we should all by now be pretty fluent in that emotional language thanks to our ability to freely splash around in endless cultural oceans: some of us toddlers in the shallows running and splashing and sitting and splashing and laughing; some of us soberly executing perfectly rigid pencil dives into bottomless lagoons, planning our exhalations and calculating the distance back to shore.

But that doesn’t feel true, despite people talking about their feelings a lot more than they used to. Berger likes to use the word ‘recognition’, but what if we don’t like what we see? What if the mirror now offers us the opportunity to edit and shape that reflection, all the while confirming that it remains real and true? And when we talk about recognition, are we referring to the moment of connection that confirms that we’re not alone, or do we now mean validation?

Here, Berger ponders Sassall’s attempts to understand the patient’s emotional state in parallel with their physical needs in order to achieve a meaningful diagnosis:

As soon as we are ill we fear that our illness is unique. We argue with ourselves and rationalise, but a ghost of the fear remains. And it remains for a very good reason. The illness, as an undefined force, is a potential threat to our very being and we are bound to be highly conscious of the uniqueness of that being. The illness, in other words, shares in our own uniqueness. By fearing its threat, we embrace it and make it specially our own. That is why patients are inordinately relieved when doctors give their complaint a name. The name may mean very little to them: they may understand nothing of what it signifies, but because it has a name, it has an independent existence from them. They can now struggle or complain against it. To have a complaint recognised, that is to say defined, limited and depersonalised, is to be made stronger.

[…]

Most unhappiness is like illness in that it too exacerbates a sense of uniqueness. All frustration magnifies its own dissimilarity and so nourishes itself. Objectively speaking this is illogical since in our society frustration is far more usual than satisfaction, unhappiness far more common than contentment. But it is not a question of objective comparison. It is a question of failing to find any confirmation of oneself in the outside world. The lack of confirmation leads to a sense of futility, And this futility is the essence of loneliness: for, despite the horrors of history, the existence of other men always promises the possibility of purpose. Any example offers hope. But the conviction of being unique destroys all examples.

Let’s sum up Berger’s paradox in two statements:

See me; read me; hear me: I am unique.

Understand me; share with me; don’t leave me alone: I am you.

(try not to read them in the voice of Roger Daltrey)

If everything is filtered through the former statement, then we’re exploring what makes us different; what makes us stand out, but with the implication that approval may relieve the isolation our uniqueness necessarily engenders. The latter statement then risks becoming performative and transactional: we think we’re sharing; we think we’re connecting, but it’s conditional on the other party first acknowledging and then validating our uniqueness. It pretends to be something else, but it’s about me before it’s about us.

American culture doesn’t even pretend to be about us; indeed, it is - and has always been - entirely predicated on the struggles, the overcomings and the achievements of the individual. In actuality what we find is a prairie-sized loneliness exacerbated by canyon-sized mythologising spread across an already vast continent. ‘Am I unique?’ has to become ‘we are unique’ and the idea of America becomes a symbolic collective ‘us’, rather than the actual people living in it, because - in the end - it’s hard to reconcile something as massive as manifest destiny, for example, with the discrete daily struggles of the self-made, self-reliant, self-serving man (echoing the gendered language of the time).

***

A great deal of [the culturally deprived’s] experience - especially emotional and introspective experience - has to remain unnamed for them.

So, what happens when, fifty years on from when Berger wrote it, everything relating to our emotional lives has been named? Arguably, our introspective experience and emotions have now not only been recognised, they've been categorised, homogenised and finally converted into currency in the form of data. Have we devalued them in this process? Have we made feelings harder to feel?

We can now bend language into shapes that mocks Sassall’s prescient diagnostic merging of the mind and body, dutifully creating new things to suffer from, so that ‘overwhelm’ transitions into a noun that we can experience as an ongoing, potentially long-term condition that we carry with us, rather than a description of something that’s temporarily happening to us. Like those male porn stars who, over time, find that they need sex to be more more extreme and outlandish to maintain arousal, are we looking too hard for ways to bypass numbness (itself - paradoxically - developed to protect us from emotional overload), or are we just more dysfunctional?

It makes me wonder. Read Berger’s description of how the village finds connection and maintains communal bonds again.

Their chief means of expression is consequently through action […] an entirely exterior mechanism or event - a motor car engine, a football match […] The very intricacy of the subjects seems to bring the speakers closer together […] and in their memory this now acquires the value of an intimacy.

I’m watching my knees for any signs of jerking, but I am sometimes so very weary of all these feelings; all the shouting; all this drama. Perhaps the intimacy Berger describes carries an emotional weight that goes beyond the meanings of the words that people say to each other, untainted by vanity, neediness or ego and fuelled by curiosity and no small amount of comfort. Perhaps connection doesn’t have to be qualified in shared trauma or a similar political outlook; surely people can just be, together, like children - interacting unselfconsciously, without having to qualify themselves intellectually or emotionally. The internet might once have been a good place to enact this, but I’m pretty sure it isn’t anymore.

Berger writes this about a successful diagnosis:

To have a complaint recognised, that is to say defined, limited and depersonalised, is to be made stronger.

I couldn’t help it. When I read that, three words appeared - unbidden - in my head:

U OK HUN?

***

Any general culture acts as a mirror which enables the the individual to recognise himself - or at least to recognise those parts of himself which are socially permissable.

Can our uniqueness co-exist with our need to connect? Of course it can - that’s the basis of all creative endeavour. But the dopamine sucker-punch of validation; the comfortable absorption into a (usually binary) political or social narratives; the ability to sculpt and refine our presence in the world; the conspicuous vanity that looms over everything when the first question is always, ‘how does this make me feel?’ - if culture is the mirror that Berger suggests, we have to remember that the glass always slightly distorts the subject in front of it: something in the eyes; the mouth is a little off; features are a little misaligned. Family, friends, lovers can always see it in our reflection but we seem unable to, so perhaps it’s worth exercising some caution when we’re looking at ourselves.

At this point, there’s not really a tidy way to gather the strands of all this speculation, and really that’s what’s made the first twenty years of this new century so interesting to observe, but often so difficult to be in. Nuance is problematic because: a) it’s hard to admit that you don’t know how you feel about something, and b) the culture is moving under our feet like the ground in a Roland Emmerich movie. It’s hard to keep your balance sometimes. The kind of extreme editorialising that social media demands doesn’t encourage subtlety, which is why a platform like this becomes so important. We get to explore questions without losing them to answers. Music does this. Books do this. Art is all about this. Why are we so uncomfortable with the uncertainty?

I don’t know, but I think I’ve finally worked out that I’m good with that.

*thank you

for the recommendation. I owe you a copy because I’m not giving this one back.

Took me 2500 words - goddamn it, and then this guy comes along…

'The stupidity of people comes from having an answer for everything. The wisdom of the novel comes from having a question for everything. When Don Quixote went out into the world, that world turned into a mystery before his eyes. That is the legacy of the first European novel to the entire subsequent history of the novel. The novelist teaches the reader to comprehend the world as a question. There is wisdom and tolerance in that attitude. In a world built on sacrosanct certainties the novel is dead. The totalitarian world, whether founded on Marx, Islam, or anything else, is a world of answers rather than questions. There, the novel has no place.'

– Milan Kundera

The dissonance of having illusory certainly in simplistic world views broken on the wheel of an unrelentingly complex reality is at tbe heart of much of today's political & social unrest. Alvin Tofler termed this as "Future Shock".

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Future_Shock