My introduction to Talk Talk went hand-in-hand with my first and only foray into petty crime. It was the late 80s and I was in Woolworths, sifting through one of those bargain bins of factory-sealed cassettes, most of which seemed to involve Neil Norman and Galaxy Gold playing disco versions of pretty much anything, when - buried under boxes populated by cowboys drinking cocktails, the Grand Canyon at sunset and bikini-clad roller skaters - something else caught my eye.

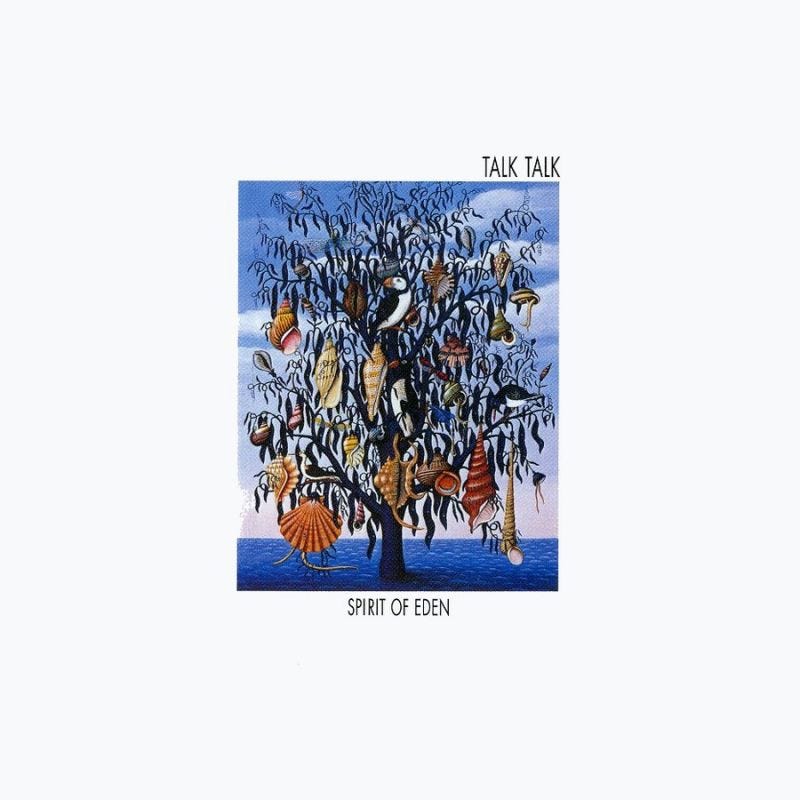

It was a dead tree rising from the middle of an ocean, with colourful seashells hanging from each of its branches. Near the top of the tree was a puffin, fixing the viewer with one beady eye. Having created quite the catalogue of disco-classical, disco-country covers and disco-movie themes, no one could say that Neil Norman and Galaxy Gold hadn’t earned a ‘troubled drug phase’, but somehow disco puffins (despite being a great band name) seemed unlikely, and this one wasn’t even wearing a leotard. I looked more closely. The album was called Spirit of Eden and it was by Talk Talk.

I knew Talk Talk didn’t I ? Lots of chilly synth pads and that chorused fretless bass sound that reminded me of an elastic band being stretched and pinged off a finger. There were billowing white shirts, ponytails, guitars strapped perilously close to chins and big choruses. They’d even written a song with the same title as the name of their band; the kind of power-move that spoke of a grand pop design. As an album title, Spirit of Eden, seemed to murmur something ethereal, incorporate and timeless; something altogether harder to pin down.

So, I now wanted to hear it. I had to have it. Music was beginning to pull away those self-consciously clasped fingers, one by one, from around my anxious teenage heart, and the promise of a mystery was often enough to drag me into a complicated and messy relationship with a new record. Or a girl, now I think about it.

Frustratingly, I’d spent my last few pounds on ten Silk Cut and a Marathon, so - quickly formulating a plan as elegant as a Paul Smith cravate - I picked up that £1.99 cassette. The plan was this: wander vaguely around the shop, weighing up tea towel options and trying on oven gloves; compare the pedal action on multiple kitchen bins; circle the Pick ‘n’ Mix like a confused shark; check my watch (why ?!), before walking out of the shop with the tape in my hand. I duly put Operation Soon-To-Be-Obsolete-Format Heist into action, gated In the Air Tonight toms ricocheting inside my chest. Yes, I was now a criminal, but this felt less Artful Dodger and more army surplus-clad Indie-ana Jones, liberating a precious artefact from under the noses of the retail Nazis.

I made it out of Woolworths, but the journey home on the bus was tense. Was the pensioner with the hairnet and the tiny dog in the seat a few rows behind me talking into her sleeve, or looking for a tissue there ? Were we going to get pulled over on the A418 by two police motorcyclists, a pursuit car and a firearms unit in an armoured van ? Half an hour later, I slipped the cassette into my tape deck, my hands still shaking. Frankly, this would have to be good. Like, eyeball-meltingly, Temple of Doom-demolishingly good in order to offset the inevitable jail-time.

That first muted trumpet note floated towards me out of a dense fog of strings, uncoiling slowly across a calm sea. Just beneath the surface I sensed - more than heard - the restless, fitful twitch of piano, strings and brass moving in tiny shoals, quickly dispersing at the anguished mammalian cries of a distorted harmonica; whispers and moans multiplying until that bluesy guitar rang out to silence them, and the drums began to break the surface of the water with their steady stroke.

Fuck.

Now he was singing, barely forming words, avoiding consonance like ancient mariners avoided seabird-themed neck wear. It was more like some kind of extended sob than any kind of conventional singing, and when the drums stopped and long tendrils of organ and double bass rose up from the water to wrap themselves around him, now pulling him gently down, it seemed as though they were bringing relief and a long yearned-for transfiguration beneath the torpid sea; all language lost to the tide.

In the second song, Eden, the wind picked up and filled the sails, eventually moving from measured calm into a storm of furious guitars, buffeting his impassioned declaration that “everybody needs someone to live by,” before dying away, his voice a passing quiver of sunlight on the water’s surface. I couldn’t understand in any conscious way what was going on, just that it moved me like no music I’d heard before. It was elemental: light, dark, earth, water, sky. I sensed that I could trust my DNA to make sense of it, even if my ears refused to.

I could hear the room they made it in. I could hear fingers on strings, air moving, vibrations, people and things - light even - taking up spaces. I could hear colours; smell earth, chlorophyll, ozone. Clocks stopped; time bent and warped to its benign gravitational pull. It was at once opaque and blurry; precise and detailed. It was quite unlike anything I’d ever heard before, and yet it felt like a homecoming, like drawing in that first deep breath through your nose when you walk into a familiar room after being away for an extended period. All my senses wanted to participate, even if they couldn’t.

Spirit of Eden has been called many things: Post Rock, ambient, slowcore; but ultimately, for me, it transcends labels by not being the sound of musicians trying to impose beauty on the world with their many learned devices and techniques, but rather the sound of human beings creating a space to put beautiful things in, an idea which - by its very nature - returns some agency to the listener: we are entrusted with certain responsibilities when we drop the needle on that run-in groove; some of that beauty has to come from us.

The word ‘Edenic’ speaks of an ideal, of things unspoilt and pure, but - running parallel to that - fundamental to any concept of Eden is the idea of the Fall. This amazing music floats on that very fulcrum, pivoting between these two ideas - much like we humans do, and it feels like a journey record rather than a destination record. I can’t think of a better way to describe it, but I promise I tried.

Talk Talk created a little map and then left it in a department store bargain bin, somewhere in the Home Counties for me to steal. If you haven’t found it yet, when you do, the map will be a different one, left somewhere else; leading somewhere else. Hopefully you won’t have to commit a crime to hear it, but if that’s what it takes, I promise - it’ll be worth the risk of hard time.

If I do get a knock on the door from the cops in the middle of the night though, I’ll deny everything.

Note: this is an expanded / improved version of a piece which originally appeared in The Spirit of Talk Talk, first published in 2012.

It's a fantastic album. I love "Laughing Stock" even more, I think. Also, Ben Wardle's book on Mark Hollis is a recommendation from my end.

It is indeed a fantastic album. I am not sure if I love this one more or The Colour of Spring. I had actually heard bits and pieces from both, but finally got the cds on a trip to Florida in 2009. Also bought Mark's solo album that day. I certainly appreciate this band a lot more after listening those cds in full.